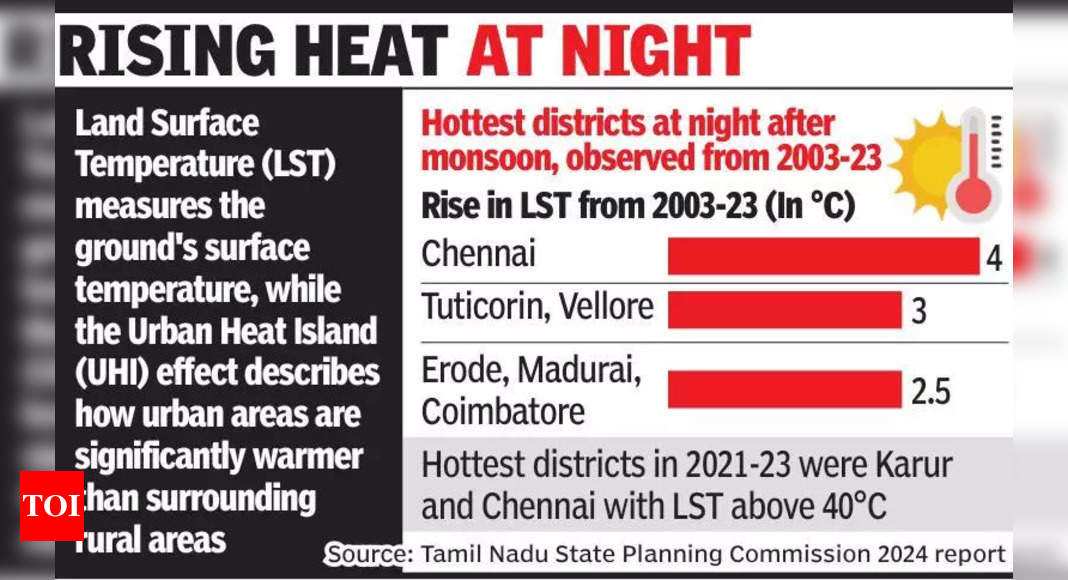

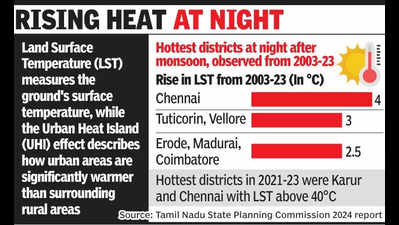

Chennai: The city’s nights have never been this hot. The average nighttime land surface temperature (LST) in Chennai has increased by 1.5°C over two decades — from 23°C in 2001–2003 to 24.5°C in 2021–2023.

This rise, driven by urbanisation and the spread of concrete-covered areas, places Chennai among the hottest districts, followed by Tuticorin and Vellore, according to the Urban Heat Island—Hotspot Analysis and Mitigation Strategies for Tamil Nadu 2024 report by the Tamil Nadu State Planning Commission.

LST refers to the temperature of the earth’s surface. During the day, the land absorbs sunlight and heats up. This heat is then released into the air, increasing air temperature, especially in densely built-up areas. At night, the stored heat is emitted slowly, preventing the air from cooling down. This explains why Chennai residents feel the heat even after sunset.

High humidity worsens the situation by trapping heat close to the surface and reducing cooling through evaporation. Water vapour in the air acts like a blanket, preventing heat from escaping, particularly at night.

Concrete areas in Chennai have grown by 70% between 1991 and 2016, covering 88% of the city’s land today. Over the same period, waterbodies shrank by half, wetlands declined by 70%, and vegetation cover dropped by 34%.

The report explains how urbanisation has intensified heat. Turning open land into buildings and roads traps heat during the day, which is then released at night, raising temperatures. Combined with high humidity, this makes it increasingly difficult for people to cool down outdoors. Tuticorin has the highest daytime LST, while Chennai’s coast places it as the second hottest in the day.

“Groundwater exploitation in Tuticorin, Coimbatore, and Madurai increases LST, as it reduces moisture in the ground and causes more heat,” said A Ramachandran, emeritus professor at Anna University’s Centre for Climate Change and Disaster Management.

The report highlights the need to restore green cover and waterbodies to cool the city. Creating more parks such as Guindy National Park and, restoring wetlands such as the Pallikaranai marshland, and pavements and buildings should be built using materials that reflect heat rather than absorb it.