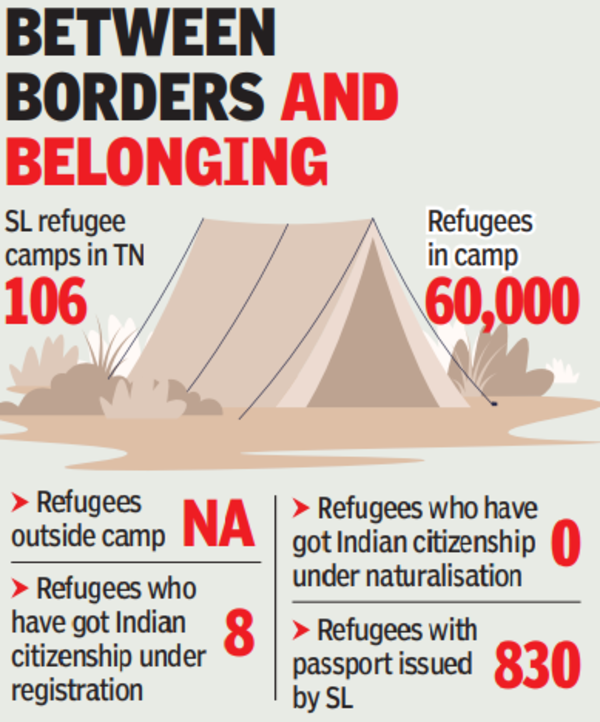

Let’s call her Kanmani*. After more than 40 years of escaping from her motherland, Sri Lanka, amid the onset of the three-decade-old ethnic civil war, she retains the island Tamil accent. And even 15 years after the war ended, she is still subjected to monitoring because she resides in one of the 106 refugee camps set up across Tamil Nadu for Sri Lankan Tamils.

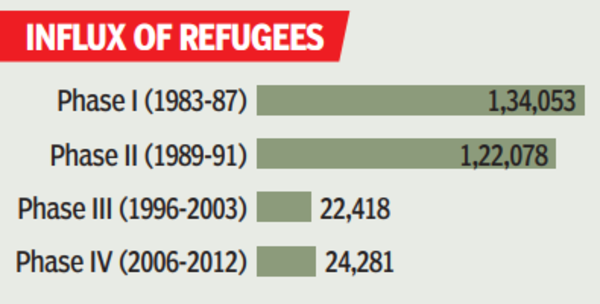

Sri Lankan Tamils migrated to Tamil Nadu in four phases: 1983-1987, 1989-1991, 1996-2003, and 2006-2012. While economic hardship still drives Lankan Tamils towards India, often to TN, the migration between 1983 and 2012 was purely due to the ethnic war.

Kanmani came to TN in the first batch. “My family fled after the ethnic clashes began in July 1983. I was eight when we arrived. In the beginning, we were put up at Adirampattinam in Thanjavur. In those days, the TN govt treated Sri Lankan Tamils like first-class citizens. We were highly respected and granted concessions such as free passes to travel on trains. Whenever there was a vacation, we used to travel to Chennai. But everything was upended after the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi,” says the 49-year-old. Since her family was well-off, Kanmani was able to complete her schooling and now involves herself in social service but says she has borne the identity of an ‘illegal migrant’ for the past four decades.

For centuries, people have migrated from one country to another, mainly due to war or internal political violence based on factors such as religion or ethnicity. To provide legal protection, rights, and assistance to those seeking refuge in other countries, the United Nations introduced the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1951. As on date, 149 countries are parties to the Convention. India was not a signatory to the Convention and hence, lacks a clear definition of refugees.

“Though we are referred to as refugees at the administrative level, legally we are identified as ‘illegal migrants’ according to Section 2 (1) (b) of the Citizenship Act, 1955,” says Padmanabhan*, a refugee in a different camp.

The Act states that an ‘illegal migrant’ means a foreigner who has entered India — with or without a valid passport or other documents as prescribed by or under any law in that behalf — but remains therein beyond the permitted time. “This identification as ‘illegal migrants’ puts people who fled from their countries in a fix. They are provided with basic needs such as food, medicine, and shelter, but are unable to access basic rights such as education, employment, and, above all, freedom,” says Padmanabhan.

“In 1989, when M Karunanidhi was chief minister, eight of our children studied medicine in govt colleges, but the quota was later abolished. Now, we only have a quota for engineering,” says Kanmani. “Today, our children can’t pursue medicine due to our refugee status. Many secure IT jobs but lose overseas opportunities because they lack passports. This is the third generation living in refugee camps, attached to the culture here, with nowhere else to go.”

Many Sri Lankan Tamil refugees have started to seek Indian citizenship. Kanmani is among them.

In India, citizenship is issued under four categories: by birth, descent, registration and by naturalisation. While the first two apply to all Indians born in India and those of Indian origin, the last two apply to foreigners.

Under the category of registration, if a Sri Lankan refugee marries someone of Indian origin, he or she can apply for Indian citizenship after seven years of residing in India. Under naturalisation, a refugee can apply for Indian citizenship after 12 years of residing in the country.

“While a few of the Lankan Tamil refugees have got Indian citizenship under registration category, the same is difficult under naturalisation because they must first renounce their Sri Lankan citizenship,” says Madurai-based advocate Romeo, who represents several Lankan Tamils. “It is emotional for many to renounce their citizenship.

Also, delays in processing the application by Union ministry of home affairs keep applicants as ‘stateless’, causing more agony.” People such as Kanmani find it even more difficult since she was ‘stateless’ even in Sri Lanka.

“My forefathers were Indians, who came to Sri Lanka to work on plantations,” says Kanmani. “After Sri Lanka became independent in 1948, they were stripped of their citizenship. Still my family held on till the war broke out in 1983.”

The second and third generation of the family, though born in India cannot get citizenship unless they satisfy the rules under the ‘by birth’ category, which is that they must be born on or after Dec 3, 2004, and if the parents are Indians or at least one parent is a citizen, and the other not an ‘illegal migrant’ at the time of birth. Many of the new generation children do not come under this ambit.

The TN govt is making efforts to help the families. The first step was changing the nomenclature from ‘refugee camps’ to ‘rehabilitation camps’ in 2021, followed by providing newly built houses and extending all govt schemes to them, including the 1,000 per month financial aid to women.

Some entrepreneurs were also granted loans from banks. The UN High Commission for Refugees’ India office in Chennai is also registering refugees and aiding them in resettlement and voluntary repatriation.

India hosts many asylum seekers and refugees from countries besides Sri Lanka, such as Tibet, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Sudan and Somalia, spread across various states. However, Sri Lankan Tamil refugees, of which there are large numbers in Tamil Nadu, appear to be faring better than those from other nations.

“The Sri Lankan Tamils residing inside the refugee camps enjoy the govt schemes like any other Tamils here,” says writer Govi Lenin, member of the state govt’s Sri Lankan Tamil Welfare Advisory Committee.

“Only those who choose to reside outside the camps are ineligible. Earlier, there were many restrictions in the camps. They are relaxed now.” Such local integration efforts by the govt for the refugees, before their naturalisation, should be welcomed, says Lenin.

While all is well, says Kanmani, true freedom will come only when the roll call stops in the camps.

(*Names changed to protect their identity)