So now you have lost the friendship as well. You are kicking yourself for having asked the question in the first place. (The stories you hear as an unofficial agony aunt!)

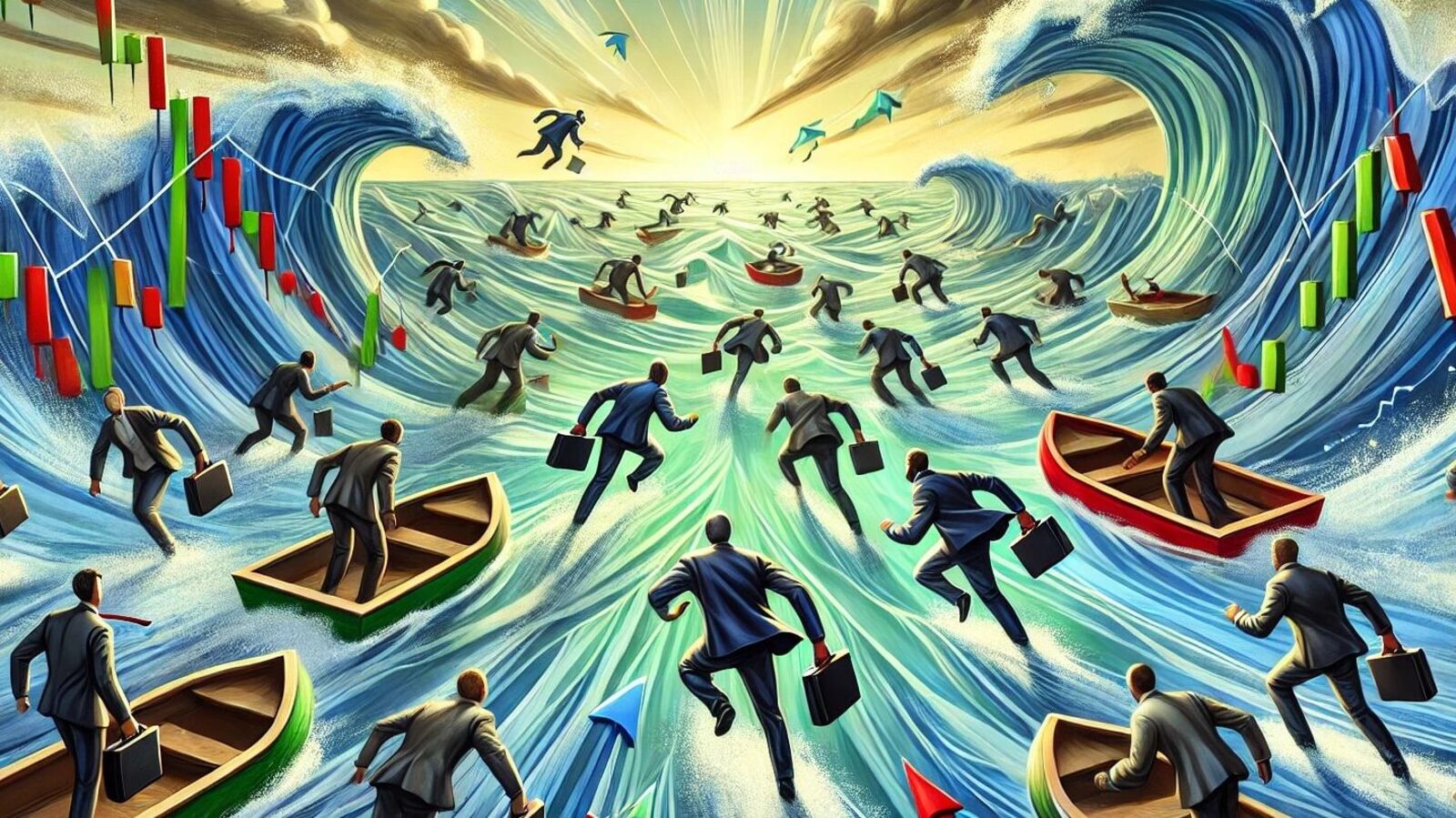

Coming to the drab realities of markets. You made an outsized investment which went down 60% and then went up a hundred fold, which meant a 40 times return.

Or, you had a chance to invest in Tesla or Apple a couple of years after their IPO and did not. And as everyone and their kid knows, they went on to be multibaggers.

Now, the question is, which one of these was a mistake? You’d be surprised to know that it is likely the second one.

What are the mistakes you have made in your investing career? This is an oft-asked question. When I think about the mistakes in my investment career, there are three aspects to consider. One involves the evolution of the investment analysis and process to come to better decisions.

The second has to do with a better understanding of hardwired human biases and thinking fallacies, and the devising of methods and strategies to get rid of those. The third is even more fundamental. It is about the definition of a mistake, and it holds for all aspects of life.

What do you call a mistake? The answer appears obvious, but it is not.

Some decisions will always go wrong. They are meant to, as the future is about known unknowns and unknown unknowns. Thus, a decision, or rather an outcome, going wrong is not necessarily a mistake. As they say in software, it is a feature, not a bug!

Once you realize this, you no longer look at a mistake being defined as a loss or an opportunity loss, but whether the process of your decision-making was incorrect, given the information you could have had at that point in time.

It inverts the lens from the outcome to the process.

In the early phases of career, in my mind, a mistake meant a decision with an undesirable consequence. For example, when you recommend a stock that did not gain, or have a sell recommendation on a stock that did not decline.

It often happened that a foreign institutional client would say that the so and so stock we had recommended did not do well.

I would mumble that it was but one of the ten stocks we had recommended over the last six months and the only one which had declined, and that for most other securities firms, the ratio was almost the other way around, but our clients would cryptically respond: “We expect better from you.”

What I did not understand well, or at least did not articulate at that time, was that this was actually a mistake of framework. Even though I saw this theoretical concept of outcomes being probabilistic in reports I wrote as far back as in 1996 and 1997, I somehow did not connect it to what the clients were saying.

The concepts of uncertainty in the stock market, of investing being a game of probability and the end result not being the same as the quality of decisions made, were later learnings.

A wrong decision can have a right outcome, and vice versa.

Over time, one realized that investing is a game of both luck and skill. Hence you are going to lose some, no matter how skilled you are. On the other hand, you may have some undeserved wins.

If you accept that and are actually geared for it, it makes your life simple and portfolio performance better.

Coming back to where I started, almost the largest amount of money that I made from my investments was on a stock (or actually a convertible bond) into which I put an outsized sum. The stock went down about 60% at a time when I was unable to sell because of a lock-in.

And from that beaten-down level, it went up a hundred times. So I made forty times my original investment. But that decision was a mistake!

The reason why it went up was totally extraneous to the analysis done at the time of investment, when it could not have been foreseen. And taking an outsized risk on it was not right either.

Many other veterans in the market have war stories of how stocks they were unable to sell due to a technical problem ended up making them tonnes of money.

On the other hand, one may have passed up opportunities to buy stocks like Tesla, which went up multifold, but the decision may not have been wrong as the company did come close to bankruptcy several times between 2017 and 2019.

And yes, the decision to bare your heart to your crush was probably not wrong either, and if it results in your getting ghosted, it doesn’t show them in very good light as a friend either.

The simplest way to improve your portfolio returns is to say every time you are buying a security that what you are expecting may not happen. If you are able to recognize this and act when the undesirable or unexpected happens, that can be a superpower.

The author is chairperson, managing director and founder of First Global, an Indian and global asset management company, and author of the forthcoming book ‘Money, Myths and Mantras: The Ultimate Investment Guide’. Her X handle is @devinamehra